What makes a work of art “Shakespearean”?

It’s a stranger question than we might think, mostly because no one agrees or realizes that they don’t agree. It’s a term that we apply across the artistic gamut, from plays to films to novels, for every age group and every genre. It seems a clever shorthand because practically everyone in the modern world knows who William Shakespeare is, and has at least read a play or seen one up close at some point in their life.

But that doesn’t actually clue us into what Shakespearean means.

It does seem a term that falls into two categories: (a) a term used to denote high quality, or (b) a term used to denote a certain type of story. Sometimes it is used to indicate both of these things at the same time. But we see it everywhere, and often reapplied past the point of meaning. When Marvel Studios released the first Thor film in 2011, it was heralded as Shakespearean. When Black Panther was released earlier this year, it was labeled the same. Why? In Thor, the characters are mythological figures who speak in slightly anachronistic dialects, and family drama is the three-dollar phrase of the hour. Black Panther also contains some elements of family drama, but it is primarily a story about royalty and history and heritage.

So what about any of this is Shakespearean?

Fair to say the term is overused. Claiming that something is Shakespearean because people talk formally is just plain silly. And Shakespeare didn’t have a claim on family drama or epic, kingdom-altering stakes when he was writing his plays, nor was he the first one to employ those devices—writing the lives of gods and kings is one of the most common storytelling choices of all. You might as well say that that every tale working with those themes is “Beowulfian” or “Ganeshian” or “Anansian”.

To suggest that the term is indicative of automatic and unassailable quality is equally misguided. No matter how incredible Henry V or Much Ado About Nothing or Sonnet 116 may be, not everything that Shakespeare wrote was all that and a pile of gold. He misstepped on occasion. Sometimes he overwrote. And what he wrote wasn’t intended to be purely highbrow; he wrote for common people, the masses, even while he wrote for royalty and nobility. He was the king of dirty jokes. Some of his most infamous zings are deliciously petty. It’s strange to watch people constantly use Shakespeare as a stamp of automatic quality when taking the term to mean “pedestrian and fun” is equally applicable.

The same goes for plots that even slightly mimic anything that Shakespeare ever wrote. The writers of The Lion King admitted to recognizing certain similarities between their tale and Hamlet, once they decided that Scar would be Mufasa’s brother. They even leaned on that similarity for a time while scripting before dispensing with it. But people still call out The Lion King for being an animated version of Hamlet, and argue the point constantly. Why? Because an uncle kills his brother for the throne and is eventually unseated by his nephew? It’s a pretty basic comparison. Plenty of stories do this kind of thing. Unless Simba actually struggles with madness, I’m not seeing much of a parallel.

The truth is, when most people say “Shakespearean” they might as well say “wow, this story is very human.” Which is great… but not particularly specific to Shakespeare or the stories he personally chose to tell.

So what about the stories that do spring directly from Shakespeare’s works?

There are many tellings and retellings and continuations and sideways looks at the works of William Shakespeare. Some of them are entirely direct in their commentaries on the Bard. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is an oft-tagged favorite. So is I Hate Hamlet. Some of these explorations delve even deeper, and then you get works like Goodnight Desdemona, Good Morning Juliet. (I highly recommend that one, if you’ve never read/seen it.) Getting a chance to see modern plays inspired by Shakespeare’s is a delightfully meta experience in and of itself, and they are often sharp in their analysis, if that’s your beat.

Science fiction and fantasy genres give us the ability to examine Shakespeare’s work through a new lens, made even easier by how often his works included magic, myth, and mystery. If you’re a fan of the classics (in film, that is), you may have noticed some similarities between Forbidden Planet and The Tempest, and you wouldn’t be wrong. Aldous Huxley famously quoted the same play for the title of Brave New World. Dan Simmons’s work frequently borrows from Shakespeare, and Harry Harrison’s “A Fragment of Manuscript” reimagines the origins of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. One of the best volumes of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman involves putting on a production of Midsummer for a faerie audience; the reality and the dream colliding to create a brand new performance.

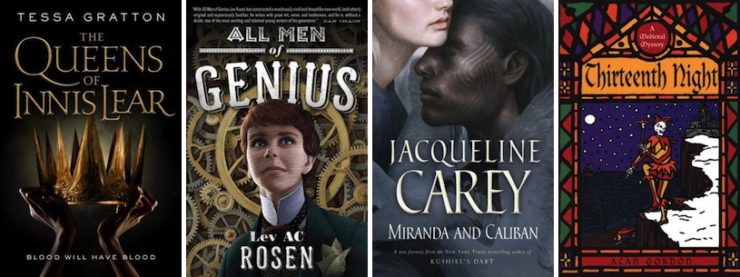

These genre-fied versions can also put a spin on the stories that didn’t grab you the first time. Tessa Graton’s The Queens of Innis Lear is a brand new look at one of my least favorite Shakespeare works, King Lear. By examining characters who may have deserved more attention in the play—namely Lear’s daughters—the book reframes the power dynamics of the original in truly fascinating ways. In another work that casts familiar characters in a new light, Lev AC Rosen adapted Twelfth Night into his steampunk Victoriana novel All Men of Genius. Jaqueline Carey’s Miranda and Caliban and Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed tell their own versions of The Tempest. Stories like these can help renew material that feels stale, or elevate parts of Shakespeare’s work that we already adore.

And what about the Bard’s stories that you didn’t want to leave? Plenty of plays and books continue to explore and expand in the space after Shakespeare’s curtain falls. Alan Gordon’s Thirteenth Night comes several years after Twelfth Night, and accompanies Feste the Fool for a brand new adventure. The upcoming Miranda in Milan by Katharine Duckett follows Prospero’s daughter in her days after their exile is ended, as she tries to navigate a new life in her father’s castle. If you find yourself reading and rereading your Complete Works of Shakespeare cover to cover, there are other avenues to pursue to find more story, more adventures with characters that you love.

However it is that you enjoy Shakespeare—through grand, vaguely inspired drama, or the more specific tales that engage with the worlds he created—there is plenty to immerse yourself in. Maybe don’t let people get away with calling every movie containing a royal family squabble “Shakespearean”, though. That’s a bit much.

Emmet Asher-Perrin is so excited to get her hands on Miranda in Milan, ya’ll. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.